Home » Articles posted by Jesse Bowling

Author Archives: Jesse Bowling

How long should you block?

One question we get a lot is “how long should we block IP’s observed by STINGAR honeypots?”

Generally, we’ve explained that we block for seven days, a number we arrived at through the highly scientific process of “I dunno…seven days sounded good and we’ve never had reason to change it”. 🙂

While more research needs to be done in this space, we do have at least one partner that showed a marked increase in the number of connections blocked by extending their block list duration from the original 24 hours. The result is intuitively unsurprising, as we would expect that it would sometimes take more than 24 hours for scanners to get from one network to another, but it’s nice to see the data laid out in a graph.

You may remember an earlier version of this graph; this graph shows roughly a doubling of connections blocked starting in May 2019, when the block time was extended from 24 hours to four days. So perhaps the magic number is between 4-7 days (which would jibe with the anecdata I’ve collected over the years), or maybe it’s not. We see good results in this range and will be leveraging STINGAR and our own network flow and block data to try and (more scientifically) identify a reasonable block lifespan.

CommunityHoneyNetwork version 1.8 released!

Hi All,

We’re happy to announce the release of version 1.8 of CommunityHoneyNetwork. This release represents four months of feature development and bug fixes. A short list of things to look out for in this release include:

- ARM support for honeypots

- “Personality” support for Dionaea (and an upgrade to 0.8)

- Persistence of custom scripts via a volume mount

- CIDR exclusions for hpfeeds-cif (so you can exclude submitting your own IP addresses, etc.)

- A new container to feed a BHR instance directly from hpfeeds (which also includes CIDR exclusions)

- More flexible file rotation options for hpfeeds-logger (including specifying time unit, or “none” to allow for rotation outside the container)

- More robust tag support (and a suggested “key-value” format)

- Tons of small bug fixes, including removal of web interface items that aren’t in use

As always when upgrading, take a look at the documentation to ensure that there aren’t new variables that need to be added to your sysconfig files; those running hpfeeds-cif will want to check out the new IGNORE_CIDR variable, which replaces the previous “IGNORE_RFC1918” variable.

Is Sharing Caring?

My three year old knows to say “sharing is caring” when his older brother is playing with a toy he wants. Sometimes it works, often it doesn’t; thankfully, sharing threat intelligence data works differently. Once the mechanism for sharing is established, it’s essentially free to share, and no one has to give up their “toy”. But do we want to “play” with other people’s “toys” when it comes to threat intelligence? </tortured_analogy> 🙂

One of the big questions people have for me on threat intelligence sharing is whether it provides value. Our own experiences here at Duke say that it does, and the limited cases where we’ve found other higher education institutions sharing their own data, we’ve found the data to be highly applicable to our own networks, with the caveats that the data is shared as close to real-time as possible, and protections are applied in an automated fashion. The key to getting value from many sources of threat intelligence data is the velocity of the data from source into protection devices.

A primary hypothesis for the STINGAR project is that if higher education networks collect information about attacks against their networks using honeypots, share that data as quickly as possible with other higher education participants, and automatically block on this data, attacks will be less effective overall. We recently received data from one of our partners which seems to back our hypothesis.

This partner has been running CHN in their environment for several months now, and decided in early December to start putting their own data into their border firewall for automatic blocking. Recently, they also decided to incorporate the data available via the shared CIF repository into their blocking rule.

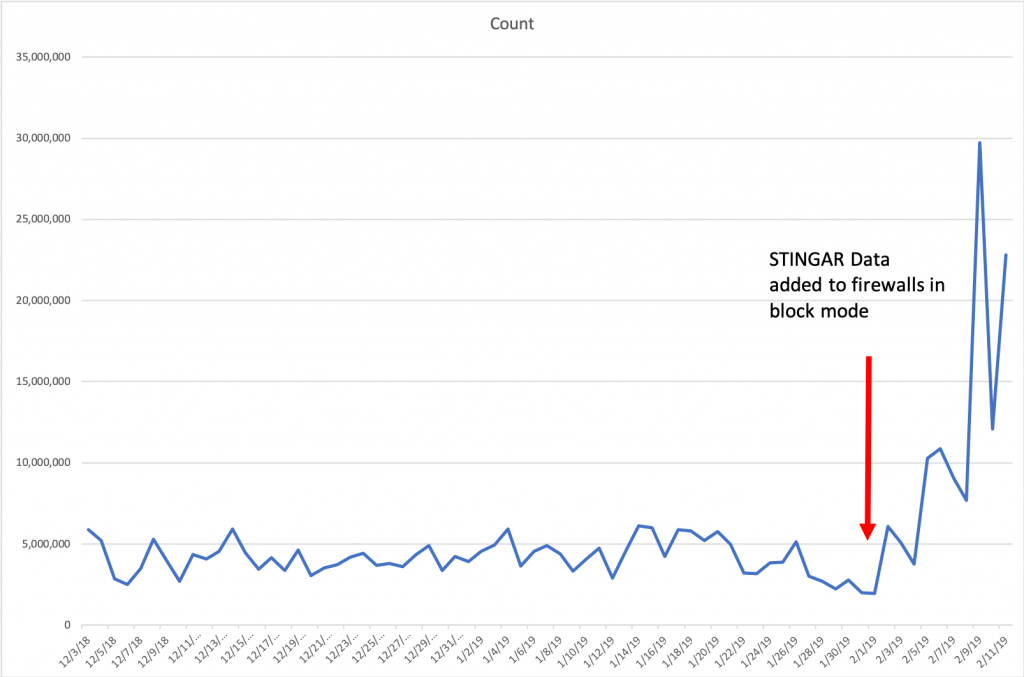

Please note: The “Count” is connections blocked per day.

So after averaging 4.1 millions connections per day blocked, inclusion of the STINGAR data pushed this average up to 11.7 million connections per day blocked, a near three-fold increase. I’m personally very excited to see this data. While we cannot know the intent of those connections, we do know that there haven’t been any reported false positives to the partner based on the blocking they’ve done. I think this is another data point (outside our own experiences) that points to high-speed sharing of data with automated blocking as a valuable tool in the network defense toolbox.

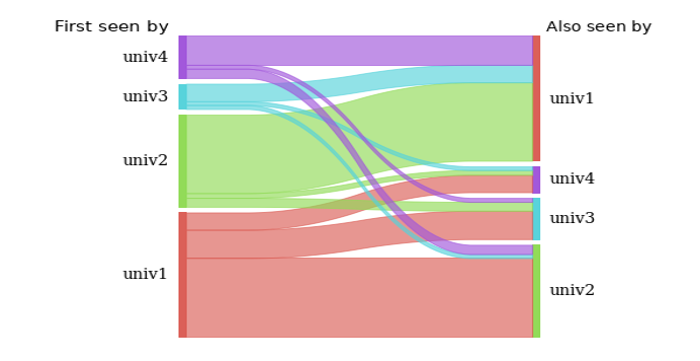

Looking for IP’s that get detected by more than one institution is another way to start to measure applicability of the data between institutions. While the number of institutions actively sharing data is still on the lower end of the scale we eventually anticipate, we’re starting to see a decent amount of IP overlap between institutional sensors.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the matter! If you’re a higher education institution you’re welcome to join our mailing list stingar@duke.edu to share your thoughts in a closed forum, or otherwise feel free to join us at Github (file an issue, or join us on Gitter).

Cheers,

Jesse

A Quick Adventure in AWS

The Friday before Labor Day, I went through the exercise of setting up a new CHN instance; the server on a local VCL-like Ubunutu 18 image, and cowrie and dionaea honeypots in each of three EC2 regions (Sydney, Singapore, Sao Paulo), and one cowrie honeypot in the same VCL IP space, for a total of 7 honeypots. All told, this took about 45 minutes (no automation on the EC2 setup, just creating a t2.nano image with minimal specs). Most of this time was spent fumbling through EC2 setup and setting up some simple bash scripts to copy/paste for the host setup. Actual time spent setting up each honeypot was probably closer to 2 minutes (mostly time spent pulling images over the network).

The following Tuesday I pulled some stats to get a sense of what those honeypots saw over the holiday weekend.

$ curl -s “http://${CHN_SERVER}/api/intel_feed/?api_key=${API_KEY}&hours_ago=96&limit=10000” |jq ‘.meta’

{

“size”: 3070,

“query”: “intel_feed”,

“options”: {

“limit”: “10000”,

“hours_ago”: “96”

}

}

This command is hitting the CHN server API endpoint to get a list of all honeypot hits for the last 96 hours. That’s not a bad haul of malicious IP’s of 96 hours. But how applicable is that data to OUR network?

First I examined incoming flow records, and found that we had inbound connections from 1055 of the original CHN IP’s in that time frame, or put another way, of all the IP’s we collected in that 96 hour period, we found that 34% of them visited our network in that same time frame. Next I compared the CHN IP’s against our threat intelligence sources for that same time period (so any locally generated threat intel from honeypots, network flow detections, host log reports, etc.) and found that in the same time frame our existing mechanisms detected 340 of these IP addresses (11% over all CHN IP’s, 32% of the locally active CHN IP’s).

In other words, our internal honeypots, threat intelligence feeds, and all other detection methods identified only 32% of the attacking IP addresses identified with honeypots distributed across multiple networks. I think this speaks powerfully to the case for operating and sharing honeypot data across numerous networks.

I’d also like to point out that our process for honeypot builds is now much easier (and more reliable). Our documentation now defaults to using images, built by us, hosted on Docker Hub, which eliminates many of the issues we saw in building the images locally. Building locally gives you a lot of flexibility to integrate into your central management as you wish, but using pre-built images GREATLY speeds spin-up time.

If you’ve been putting off trying out CHN, please set aside a couple hours on your calendar to try it out. If you ARE using the system today, it would be great if you could share your stories with us.

— Jesse